Bhutanese Traditions

Bhutan is a culturally rich society with a sense of deep respect and value for age-old culture and traditions. Having always been politically independent, a rich and distinctive culture developed in the country and citizens pride in the preservation of their valued heritage. Some of the unique traditions are:

National Dress & Types of Ceremonial Scarves in Bhutan

National Dress & Types of Ceremonial Scarves in Bhutan

Bhutan’s national costume is deemed very important in the preservation of its culture and national identity. The traditional dress for men is the 'Gho', a knee-length robe tied with a handwoven belt, known as 'Kera'. Under the Gho, men wear a Tegu, a white jacket with long, folded-back cuffs. Women wear the 'Kira', an ankle-length dress, a large rectangular cloth clasp together by a 'Koma' (brooches). The Kira is often worn with colourful blouses called 'Wonju' alongside a 'Tego' (an outer jacket). The textiles are mostly hand woven and intricately designed by talented weavers throughout the country.

While visiting the Dzong or Government offices bearing the national flag, Bhutanese wear the national costume with ‘ceremonial scarves.’ Men wear a silk scarf called ‘Kabney’ from the left shoulder to the hip and women wear a ‘Rachu’, a narrow-embroidered cloth draped over the left shoulder. The rank of the bearer determines the colour of kabney or rachu that he or she wears.

His Majesty the King of Bhutan (Druk Gyalpo) and the Chief Abbot (Je Khenpo) wears a saffron scarf.

The dark green scarf is worn by judges.

Deputy Ministers and Ministers wear orange scarves without fringes.

Members of the National Assembly and National Council wear a dark blue scarf.

The red scarves (Bura Marp) or red-gold (Lungmar) scarves are awarded to outstanding individuals in recognition of their excellent service to the nation. It does not represent a wearer's post. And individuals who are awarded either the Bura Marp or Lungmar scarf are given the honorary title of Dasho conferred by His Majesty the King. ‘Lung-mar’ is a compounded form of two words, lungserma (red-gold) and Marp (Red).

The district administrators and governors (Dzongdag, Drangpon, Dzongrab, Drungpa), wear a white scarf with fringes and red band with one, two or three stripes.

For village chiefs (Gups), the scarf is red with fringes and two broad, red vertical borders known as khamar.

The commoners wear a white kabney (males) while the females wear colourful rachu with intricate design.

Titles and Form of Address

Titles are extremely important in Bhutan. All persons of rank should be addressed by the appropriate title followed by their first or full name. Members of the Royal Family are addressed as ‘Dasho’ if they are male, and ‘Ashi’ if female. A minister has the title ‘Lyonpo’.

The title ‘Dasho’ is also given to those outstanding individuals who have been honoured by His Majesty The King and awarded with a red scarf. Senior monk or teacher is addressed with title ‘Lopon’ (pronounced ‘loeboen). A 'Trulku' (reincarnate lama) is addressed as ‘Rinpoche’ and a nun as ‘Anim’.

A man is addressed as ‘Aap’ and a boy as ‘Basu’, a woman is addressed as ‘Am’ and a girl as ‘Bum’. While calling an individual whose name is not known one may address as ‘Ama’ for women and ‘Aaap’ for men. In the same situation, girls can be addressed as ‘Bumo’ and boys ‘Alou’.

White silk scarves called 'Kata' exchanged as customary greetings among ranking officials and offered to high lamas as a sign of respect.

Status of Women in Bhutanese Society

Status of Women in Bhutanese Society

Bhutan has an egalitarian society and Bhutanese women constituting about 49.5 per cent of the country’s population play a major role in the development of the country. Women are actively involved in all areas of economic, political and social life as entrepreneurs, farmers, engineers, doctors, politicians, decision-makers and homemakers. Law of the land treat women and men equally and there is no discrimination based on gender. The participation of women at different levels of administration is being encouraged and it is continuously rising.

There is no significant preference for the male child over the female among most sections of the population and sex-based abortions are unknown in Bhutanese society. In traditional society, most of which is matriarchal, women were expected to hold the house and landed property while sons would leave home and settle in their wives' house. This custom is based on the belief that women need economic security to enable them to take care of their parents and raise children. This has led to the customary rights of importance by daughters.

The National Women's Association of Bhutan (NWAB) was established in 1981 to enhance the role of women at all levels of the development process. The association with nationwide chapters has successfully addressed the various needs of rural women through a variety of programs like education, family healthcare, skills training, employment and rural credit facilities.

Social life in Bhutan

To date, Bhutan has retained many of its traditional social structures and has actively sought to preserve its cultural identity in the face of modernisation and increasing external influences. In many ways, Bhutanese society is a large interwoven family with strong community bonding where they celebrate together happiness, success and work. It is usual to see locals even greeting strangers and offering tea and drinks especially in the villages and often said that Bhutanese would offer tea even to their enemies. When relatives, family members and acquaintances return to villages after a long time or children returning home from studies, it is usual to see people gathering and celebrating the occasion. Most of the families in western Bhutan host annual rituals which provides an opportunity for family members to get together who have been away from home due to work or study.

Buddhism permeates everyday life in Bhutan. Prayer flags flutter throughout the country, prayer wheels powered by mountain streams clunk gently by the roadside, images of Buddhist Gurus cared into a cliff, reminds that every aspect of daily life is shaped by Buddhist beliefs and aspirations. Though Buddhism is practised throughout the country however most Bhutanese people of Nepalese origin practise Hinduism and in fact, major Hindu festivals are marked as National holidays in the country.

Until the 1960s, there were no major urban settlements in Bhutan but with the growth and development of road infrastructure few major towns have sprung up. Also, as a result of opportunities created by education and infrastructural development, the country has experienced significant social mobility in recent decades from villages to urban centres. But despite rapid urbanisation, the majority of people still live in rural Bhutan and most are dependent on the cultivation of crops and livestock breeding. Traditionally, Bhutanese have been self-sufficient and there remains a degree of self-sufficiency among the rural Bhutanese though in urban centres, many everyday items are now imported from India, Thailand and Bangladesh also.

Marriages in Bhutan

Steeped in tradition, weddings in Bhutan are richly infused with elements of Buddhism. Wedding ceremonies typically involve a whole set of religious rituals performed by Buddhist monks and lamas. It is an important social occasion where the family, relatives and friends of both the bride and groom actively participate. For the Bhutanese, a wedding ceremony is not just a simple exchange of vows and rings followed by a lavish spread with lots of merrymaking, drinking and dancing. A traditional wedding encompasses the following ceremonies:

Firstly, an auspicious date after reading the 'Datho' (daily astrology book) according to the Bhutanese calendar is picked up for the wedding. Depending on the wishes of the couple, the ceremony can be conducted either in a Kyichu Dzong (Monastery) or a Druk (Dragon) Choeding temple.

Lhabsang Ritual: This ritual starts early on the auspicious day chosen for the wedding. Monks chant mantras as they burn incense and make offerings to the local deities. All these rituals are performed outside the temple or monastery, prior to the arrival of the bride and groom. It is generally believed that if the local deities are satisfied and pleased, the couple will be blessed with love and happiness throughout their life and the wedding ceremony will go smoothly.

Lighting of Butter Lamps: Once the bride and groom arrive, the butter lamps lighten after they have prostrated six times – three times at the Head Lama or Guru Rinpoche and three times at the main altar of the temple or monastery. It's an important ceremony and symbolises the illumination of a couple’s life ahead together.

Thrisor Service: Following the lighting of butter lamps, the Head lama and few monks perform a Thrisor service. This purification ritual is believed to cleanse the couple’s body, speech, mind, soul and most importantly make them free of all their sins.

Changphoed Ritual: In this interesting ritual, locally brewed alcohol or 'Ara' is offered to the deities. The remaining brew is served to the bride and groom who drink from the same phoob – a traditional wooden bowl. The Changphoed ritual signifies the close bond that the couple will share for the rest of their lives and this is followed by the exchange of wedding rings – meant to bind the bride and groom together.

Tsepamey Choko: Performed by the Head Lama, ‘Tsepamey Choko’ refers to the God of Longevity in Bhutan and as the name suggests, this ritual signifies the blessings granted to the couple for a blissful, lifelong marriage.

Zhugdrey Phunsum Tshogpa: Also known as ‘Zhungdrey’, the Zhugdrey Phunsum Tshogpa is a food sharing ritual. To begin with, the fruits and food are served to the local deities, then to God and finally to the guests who have turned up for the ritual. Fruits used for the ceremony are usually oranges, meant to represent the sweet bond between the couple. It is also customary for guests to accept the fruits as a sign of goodwill.

Dhar Nyanga presentation: The ceremony ends with the presentation of the Dhar Nyanga (scarves) to the bride and groom along with best wishes for a happily married life.

Naming Process of People in Bhutan

Naming Process of People in Bhutan

Unlike in many other countries, where surnames become an important part of a person’s name, names in Bhutan do not necessarily carry any surnames. Most Bhutanese have two names but there are many others having a single name only. The first name could be the same for both genders while the second name may help to identify the gender of a person.

Most names in Bhutan have meanings associated with Buddhist religious figures, beliefs and Gods including Buddha himself. Buddha in Bhutan is known as 'Sangay' and many people have this name, which means ‘have attained enlightenment'. Similarly, there are names like 'Karma', associated with the Buddhist belief of rebirth based on good or bad deeds. 'Deki', which means peace and happiness, is also a common name like 'Sonam' which means luck. 'Pema' too is a common name that means lotus and refers to purity. 'Dechen' means ‘great compassion’, Tashi means good auspicious or good luck, 'Sonam' means ‘religious merit’, 'Chimi' means immortality, 'Tshering' means long life, 'Ugyen' is the saint Padmasambhava, 'Dorji' is the state of indestructibility, are other popular names.

Bhutanese personal names are quite limited and only about 50-60 names are in existence so there could be a number of persons with similar names. Except for Royal lineage, generally, Bhutanese names do not include a family name. Unlike in many other countries, a woman does not take her husband’s name after marriage and even children’s names could be totally different from their parents.

According to traditional belief, a newborn is named within few weeks after birth and names are given by a lama or religious master. The horoscope of the baby is also prepared by a local astrologer which contains details of the child’s previous life, present life predications and various important stages and events of life.

Family System in Bhutan

The strong family bonding permeates every facet of Bhutanese society. The notion of family in Bhutan is much more subtle than merely a family unit or nuclear family. It includes an efficient, close-knit, interdependent structure as if all are related and this is rightly the best way to survive in the rugged terrain and isolated far off villages and remote areas.

The structure of the family and members dependence on it remains intact in Bhutan and has not yet gone the way of nuclear family and isolation but the family is still thriving in Bhutan and is one of the most important social structures tied to culture, governance and the environment. Notably, Bhutanese have a natural inclination to treat others with intimacy and familiarity as if they all are one family.

A typical Bhutanese family in villages would consist of the following members, all living together and enjoying life: 'Agay' (Grandfather), 'Angay' (Grandma), 'Apa' (Father), 'Ama' (mother) and 'Alu' (Children). Life in a typical Bhutanese village begins with 'Dola' as the rooster crows and Dola means attending to miscellaneous tasks like attending to a kitchen garden, milking the cow, churning the milk for butter, grinding the grains, changing water offerings in the altar etc. The parents return for breakfast only after the Dola is completed. After breakfast, elders leave for the main work while children attend school or do other chores. If the family works in field then they usually eat outdoor lunch. Families eat dinner mostly in the kitchen, sitting on the floor around the oven with crossed legs on a wooden floor. They put all the pots and pans in the middle and then the mother or grandmother serves everyone. Before eating, a short prayer is offered, and a small morsel is placed on the floor as an offering to the local spirits and deities.

However, in changing times of greater education and development Bhutan is also experiencing social mobility in recent decades and rural-urban migration continues to increase impacting the culture of a joint family system.

Birth, Death & Rebirth

Birth, Death & Rebirth

The birth of a child is always regarded as a welcome event. When a child is in the mother’s womb, Buddhist scriptures like 'Domang' are read by 'Chops' (the religious practitioners) in the house of pregnant women with the objective to have good birth of a child and to avoid any complications. It is customary that pregnant women do not disclose the pregnancy news until the advanced stage and it is common belief that if a woman talks about the birth of a child, it may invite bad luck and harm to the child. On the third day of the child’s birth, a short purification ritual is performed after which visitors are welcomed to visit the newborn and mother. In about a week, a 'Tsip' (astrologer) after consulting the scriptures, suggest a day when the child can be taken outside the house. The Tsip also records the time, day, month and year of the child in accordance with the Bhutanese lunar calendar to make a 'Keytsi' which is a document that incorporates all the important details relating to the time of birth, birth sign and child’s future predictions. The child is usually named by the head lama of the local temple and also mother and child receive blessing from the local deity. Traditionally name associated with a deity is given to a child while in some cases, the child is given the name of the day on which he or she is born.

Death is believed to be a transition from one body to another but is still it is a sad affair except if the person is highly spiritual and believes in getting liberated from the limitation of the body and getting enlightened upon death. As soon as the death occurs, the monks, nuns and other religious practitioners are immediately called to read 'Bardo Thodrel' (book of the dead). The 'Tsips' (astrologers) are usually consulted to find the proper time and day for cremation. Since it is believed that death is a transition period before going into the next birth so utmost care is taken to follow the Tsip’s readings. The 7th, 14th, 21st and 49th days after a person’s death are considered especially important and are recognized by erecting prayer flags in the name of the deceased and performing specific rituals. It is believed that the dead spirit on each seventh day gets more active and is likely to proceed to the next birth while on other days, it wanders in dilemma and is not able to decide and finds its way. Therefore, the lama, who is conducting funeral service and ritual for the deceased guides to deceased’s spirit. The lama reads the 'Bardo Thodrel' (book of the dead) which is believed to liberate the dead from the predicament by just hearing it. As per local belief, many souls wander about because of their attachments to people and belongings and in order to help the dead to find their way to the next life, various rituals are performed which helps in breaking the past life attachments. In affluent families, prayers are conducted up to the 49th day and then on this day funeral services are done in temples and monasteries. The ashes of the deceased are usually collected and pour into the river following some reading of scriptures or in some cases put into a statue and donated to the monastery or temple dedicating to the deceased. Elaborate and ancient rituals are also conducted on the anniversary of the death with the erection of prayer flags.

Bhutanese people follow two major religions; Buddhism & Hinduism which have many similarities in many beliefs and faith and both believing in compassion, karma, and rebirth. In Bhutan, the Northerners are mostly Buddhist while the Lhotshampas in the south practise Hinduism. Buddhists embrace the concepts of 'Karma' (the law of cause and effect) and reincarnation (the continuous cycle of rebirth). The law of Karma dictates that an individual's decisions and behaviours in one life can influence his or her transmigration into the next life; for example, if someone lived life in harmony with others, that person would transmigrate to a better existence after death. In contrast, someone who had lived selfishly would inherit a life worse than the previous one after death. One central belief of Buddhism is often referred to as reincarnation - the concept that people are reborn after dying. In fact, most individuals go through many cycles of birth, living, death and rebirth. A practising Buddhist differentiates between the concepts of rebirth and reincarnation. In reincarnation, the individual may recur repeatedly. In rebirth, a person does not necessarily return to Earth as the same entity ever again.

Popular Bhutanese Beliefs and Superstitions

Certain local beliefs and superstitions play an important role in Bhutanese society and are part of the country’s subculture. Some of the popular beliefs and superstitions are:

Losar - the New Year in Bhutan

Losar - the New Year in BhutanThough different regions of Bhutan celebrate the new year at different times of the year. For instance, Nyinlo (Winter Solstice) is the new year observed by people of Thimphu, Punakha, Wangduephording and Trongsa, Lomba is celebrated as new year by communities of Paro and Haa district while Eastern Bhutan celebrates Chunyinpi Losar (Traditional day of offering) as New Year.

The Losar New Year celebration begins with Nyi Shu Gu (Losar New Year’s Eve) and continues, in some parts of Bhutan, for two full weeks. The first three days of the New Year have the biggest celebrations in Bhutan though official holidays are observed only for two days. Tibetans celebrate New year for 1 week and all Tibetan institutions are closed during this period.

The origins of Losar can be traced back to the pre-Buddhist period and the Bon religion and was most likely celebrated to mark the winter solstice. When the region converted to Buddhism, the date was shifted by Buddhist monks to match up with their lunar calendar.

As Losar New Year approaches, locals begin preparation by cleaning their homes and making special offerings at temples called ‘Lama Losar.’ Temples and monasteries are ornately decorated for the occasion, and special ‘puja’ rituals are performed at the monasteries.

On New Year’s morning, breakfast is taken just at sunrise, and various rituals are observed. A meal at noon and a mid-afternoon snack are also traditional. Families often go on picnics together, and it is a day that mixes celebration with relaxation. Losar is also a perfect time to try various delectable Bhutanese staple dishes such as stews, ema datshi (chilli-cheese), red rice and sweets. Locals make a variety of homemade cookies for offerings and to share as a New Year gift with relatives and neighbours. People of Tibetan origin also prepare elegant and elaborate artistic cookies for offerings and exchange amongst friends and relatives. According to tradition, green bananas and sugarcane should be present on a New Year's table, as they bring goodness for an upcoming year. The first lunar month is also observed as a holy month and consumption of animal flesh is totally avoided. The majority of the Bhutanese turn vegetarian for this entire month and meat stalls are closed by law.

Later in the day, local Losar festivals are held all over the nation, where there is abundant feasting, singing, and dancing. Games such as darts and archery are played, archery especially being prominent because it is the national sport of the country. Everyone greets each other with ‘Tashi Delek!’ which is a wish for abundance and good luck.

New Year in Bhutan is an ideal time for family reunions and the strengthening of cultural rituals and ties. It is also one of the biggest family get together in villages with lots of feasting and this period also coincides with lean season for farmers engaged in agricultural work so plenty of time for relaxation and merry-making.

Doma-Pani

'Doma' is an integral part of Bhutanese life culture; it is chewed everywhere, by all sections of society on all occasions. 'Doma Pani' has three main ingredients: Doma or Areca Nut (Areca catechu), Pani or Betel Leaf (Piper betel), and Tsune or Lime (Calcium Carbonate). A formal offering of Doma-Pani is made by tying three piper leaves with their tips separate and stalks together along with a full or half betal nut with a pinch of lime is placed on it. Traditionally, Doma is prepared and kept in a 'Bangchung' (container/plate made of bamboo) and served one by one to every guest respectfully.

Doma, in fact, equivalent to Indian Paan, serves as an ice-breaker at social gatherings and meetings and has become an essential part of Bhutanese life & culture; it is served after meals, during rituals and ceremonies, chewed at workplaces by all sections of society and acts as a good casual gift amongst friends or strangers.

Doma is believed to keep people warm in colder climates and have some benefits if consumed after meal once or twice a day to provide calcium supplement and helping in digestion as well but excessive chewing of Doma could be harmful to health. Repeated use of Doma could lead to high blood pressure, stress and disturbs the smooth function of other vital body organs. Doctors strictly warn people suffering from diseases of intestinal tracts like ulcers and gastritis not to indulge in excessive doma chewing.

In Bhutan, Doma chewing defies time and space, age and gender. And nobody exactly knows how, why and when doma became such a fundamental part of the Bhutanese culture and ethos. Though historical records suggest that offering doma-pani became a tradition since 1639 when the construction of Punakha Dzong was completed, and a consecration ceremony was held. Zhabdrung friends from Bihar (India) are believed to have gifted him doma-pani and since then it has been used in most formal ceremonies like marriages, promotions and other occasions and became an integral part of Bhutanese culture.

Seven Bowls of Water Offering

Making offerings is one of the most common practices that Bhutanese people follow in their daily lives. Every offering has a specific meaning and purpose. For instance, offering light is to dispel the darkness of one’s ignorance, offering incense to enhance one’s ethical behaviour.

Yonchab or ‘water offering’ is believed to be prevalent since the time of Buddha. One of the reasons why the water offering is more in practice is that water is the cheapest thing which even poor people can afford and also because the rich can avoid boasting of their wealth.

The water offering in seven bowls represent:

* Drinking water: It is believed to create auspiciousness and bring positive effects and attitudes to one’s mind.

* Water for washing hands: This is clear and clean water mixed with incense or sandalwood which is made as an offering to all enlightened beings’ feet. It symbolizes purification and believed that by making offerings to clean the enlightened beings’ feet, we are actually purifying our minds.

* Flowers: It symbolizes the practice of generosity and is believed to open our hearts.

* Incense: It symbolizes moral ethics and discipline.

* Lamp: It signifies the stability and clarity of patience, the beauty which dispels all ignorance.

* Perfumed water: Offering of perfume or the fragrance from saffron or sandalwood. It signifies perseverance of joyous effort. Through that one quality, one develops all the qualities of enlightenment.

Food in the form of torma: Offering food that has a lot of different tastes signifies nectar or ambrosia to feed the mind.

Prayer & Meditation

Prayer & Meditation

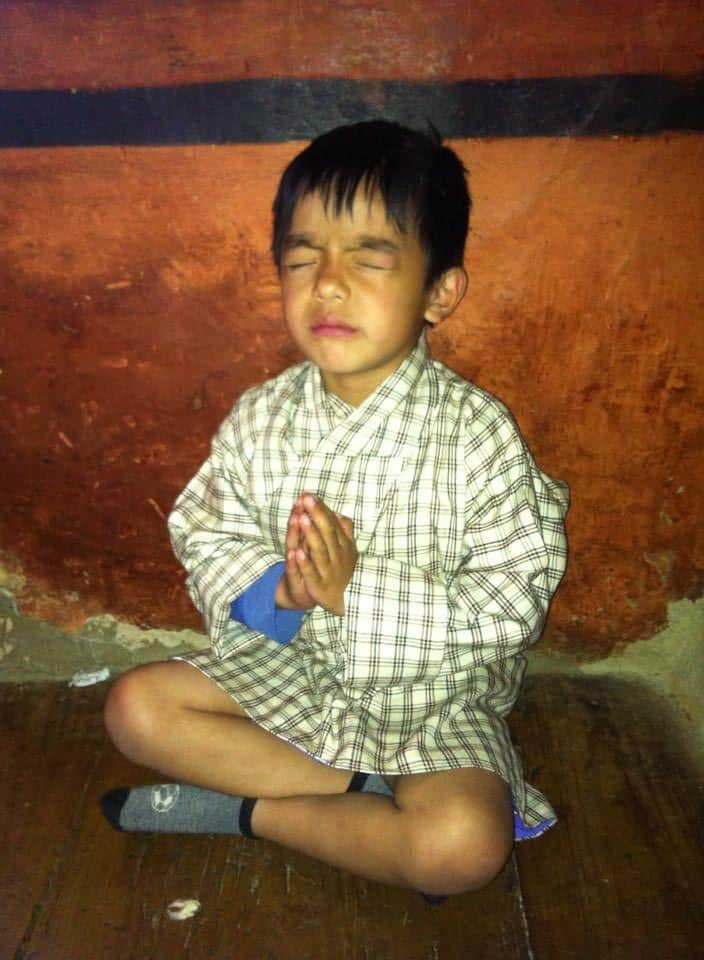

Most Bhutanese engage in prayers, in one form or another. Prayer helps a person to repent past transgressions and also guides one not to repeat them. It is also a means to communicate ritually with Buddha and Bodhisattvas. There are no prescribed times for prayers but in daily lives, most people do prayers in the morning or evening. They also take time to go and pray in the monasteries and temples on auspicious occasions. People also pray before meals or sometimes before going to bed. Most Bhutanese, like other Buddhists across the world, use prayer beads while praying.

While praying, most Bhutanese fold their hands into lotus form which is a sign of showing respect, concentrate one’s mind and heart and open them for the teaching of Buddha. The chanting of prayers also gives an opportunity to learn, reinforce, and reflect upon various Buddhist teachings. Texts like Kanjur (the teaching of Buddha), Tenjur (commentaries on various teachings), and Dema (Praise for Tara, the Goddess of compassion) are often recited.

The rosary in Bhutan is called 'Chengm' and is part of many people’s daily practice. The rosary contains 108 beads which are divided into four sections of 27 beads. The 108 beads on the main string are explained by the repetition of the sacred spell 100 times and the extra 8 are to ensure that there is no omission or breakage in working the spell.